Last year, what was billed as the final season of American Idol – at least until ABC picked it up after its storied run on FOX – aired over the course of a few months.

I had watched bits and pieces of the first few seasons as a teenager. But I didn’t really start keeping up with the show more regularly until its final three seasons, after Harry Connick, Jr. (who knew a few things about music theory and not just singing or stage presence) came on board as a judge. Throughout those last episodes, the show periodically stopped to look back on some of its most memorable highlights.

I had watched bits and pieces of the first few seasons as a teenager. But I didn’t really start keeping up with the show more regularly until its final three seasons, after Harry Connick, Jr. (who knew a few things about music theory and not just singing or stage presence) came on board as a judge. Throughout those last episodes, the show periodically stopped to look back on some of its most memorable highlights.

And that’s when it hit me: fame in 2001, when Kelly Clarkson won, was a different beast than fame in 2016, when Trent Harmon won.

In the age of overnight social media sensations like Chewbacca Mom, the fleeting nature of fame has become much more apparent. Structured singing competitions like Idol, with their promises of superstardom, seem antiquated in an increasingly cynical world where anyone could rise to and fall from prominence on social media within a week. Similarly, Hollywood has experienced its own image makeover. Idealized dreams of fame and fortune, which once took center stage in musicals like The Muppet Movie, have been tempered by the harsh, cold reality of managing life in the real world, as glimpsed in last year’s La La Land.

In the age of overnight social media sensations like Chewbacca Mom, the fleeting nature of fame has become much more apparent. Structured singing competitions like Idol, with their promises of superstardom, seem antiquated in an increasingly cynical world where anyone could rise to and fall from prominence on social media within a week. Similarly, Hollywood has experienced its own image makeover. Idealized dreams of fame and fortune, which once took center stage in musicals like The Muppet Movie, have been tempered by the harsh, cold reality of managing life in the real world, as glimpsed in last year’s La La Land.

I’m going to issue a challenge to my fellow Jesus-followers in a few paragraphs, and it might make some feel uncomfortable.

Normally I’m not one to suggest a divide between “sacred” and “secular” spheres. But I’d like to use those terms here to draw a distinction – and a comparison. In the secular space, specifically Western civilization, we’ve witnessed a society that collectively celebrated and placed their trust in human achievement and effort gradually evolve into a more cynical one. The accessibility of information and ease of storytelling has made the brevity of life and fleeting nature of fame startlingly clear. The pursuit of significance through fame has morphed into a pursuit of significance by virtue of leaving a legacy – doing something that will make a long-lasting impact after we leave this earth.

In the sacred space, Christians have traditionally subscribed to the understanding that human life is finite and limited, meant for something beyond this world – and the idea of legacy ought to reflect that. Beneath that understanding are many different approaches for living life and engaging with culture. Some might be more fatalistic in their view – this world will end one day anyway, so what’s the point of bettering it? – either assimilating into culture without a second thought, or fortifying themselves and refusing to engage with it. Some might be more dominative in their view, engaging with culture to drown out and silence those who have an opposing viewpoint. Others might be more transformative, contributing to culture to improve it and live out the Gospel.

In the sacred space, Christians have traditionally subscribed to the understanding that human life is finite and limited, meant for something beyond this world – and the idea of legacy ought to reflect that. Beneath that understanding are many different approaches for living life and engaging with culture. Some might be more fatalistic in their view – this world will end one day anyway, so what’s the point of bettering it? – either assimilating into culture without a second thought, or fortifying themselves and refusing to engage with it. Some might be more dominative in their view, engaging with culture to drown out and silence those who have an opposing viewpoint. Others might be more transformative, contributing to culture to improve it and live out the Gospel.

No matter what sphere you’re in or what perspective you hold, the fleeting nature of our life here is something of which we’re becoming more aware – and our response to that realization informs much of how we live day to day. But I want to focus on one area in particular: our creative nature. If fame and life in general are so fleeting, then what is our creativity – our contribution to culture – actually for?

I’m concerned that in our society of consumers, it’s become all too easy to leave the work of building culture to those we label “creative people.” It’s easy to segment and compartmentalize different types of vocations, categorizing some as creative and placing everything else in its appropriate box. If we don’t see ourselves as a part of the “creative box,” our natural bent is to consume the creative output (read: goods and services) of others, supporting those from whom we want to see more and avoiding those from whom we want to see less. And while that’s kind of a part of life in this culture, I can’t help but wonder if we were made for more than just that.

I’m concerned that in our society of consumers, it’s become all too easy to leave the work of building culture to those we label “creative people.” It’s easy to segment and compartmentalize different types of vocations, categorizing some as creative and placing everything else in its appropriate box. If we don’t see ourselves as a part of the “creative box,” our natural bent is to consume the creative output (read: goods and services) of others, supporting those from whom we want to see more and avoiding those from whom we want to see less. And while that’s kind of a part of life in this culture, I can’t help but wonder if we were made for more than just that.

Personally, it’s hard for me not to feel conflicted whenever my brothers and sisters in the faith lash out at Hollywood after a politically or religiously charged disagreeable statement from an actor or director is made. On one hand, some of that criticism is indeed deserved. But there are a couple of pitfalls that can easily accompany it. If you’re distant from that world, there’s a tendency to view Hollywood as a monolithic entity with a singularly focused agenda – and to feel threatened by it. If you’re more connected to pop culture, there’s an equally unhealthy temptation to personalize its players on an individual basis – crafting idealized images of those you support, being disappointed whenever those images aren’t congruent with reality, and moving on to the next product to consume.

But what if there were another way? What if people who exist in the creative box – including Hollywood – are just like you and me? What if they’re just as broken and in need of a Savior? What if they, whether or not they realize it, also bear the image of their Creator? What if their capacity to create, even when we may at times take issue with the final output, is a key part of that image?

If we as followers of Christ are going to be a part of His redemptive plan for the world, our view of creativity has to differ from society’s, and on a more foundational level, our view of work has to differ as well. Whether you’re an artist, a carpenter, a janitor, or a programmer, work in God’s economy isn’t merely a utilitarian function to keep society stable or to provide for only ourselves. Work itself is something we are created for. It’s a gift from God to discover our callings and to benefit others and meet their needs, even in the context of a fleeting, short life. It’s an inherently creative and collaborative effort, regardless of what vocation is involved. And while it can be personal, it never exists in a vacuum. It necessitates relationships as part of the creative process. It’s a part of a much larger ecosystem that ultimately plays a key role in God’s redemptive story: culture.

If we as followers of Christ are going to be a part of His redemptive plan for the world, our view of creativity has to differ from society’s, and on a more foundational level, our view of work has to differ as well. Whether you’re an artist, a carpenter, a janitor, or a programmer, work in God’s economy isn’t merely a utilitarian function to keep society stable or to provide for only ourselves. Work itself is something we are created for. It’s a gift from God to discover our callings and to benefit others and meet their needs, even in the context of a fleeting, short life. It’s an inherently creative and collaborative effort, regardless of what vocation is involved. And while it can be personal, it never exists in a vacuum. It necessitates relationships as part of the creative process. It’s a part of a much larger ecosystem that ultimately plays a key role in God’s redemptive story: culture.

It’s impossible to separate oneself completely from that ecosystem. Whether or not we intend to do so, we contribute to culture each and every day. The challenge is this: where are our hearts when it comes to the work in which we engage each day and the way we contribute to culture?

Do we work simply because it benefits us, or because it serves a greater purpose? Do we work to tend our bodies, or to shape our souls? Do we engage with culture to respond, or to contribute? Do we create because we want to redeem culture or because we want to build our own subculture? Do we develop the gifts and talents God has entrusted to us, or do we bury them and focus instead on how others use theirs? Do we create because we want to achieve an end result or send a message, or because we want to reflect and share the joy our Creator felt when He created us?

Where are our hearts?

Storming off in a huff, I returned home with vengeance at next year’s race at the top of my priority list. While at a local county fair, I studied all the Boy Scouts’ top designs and how aerodynamically sound they were. I joked around with friends about how we could sabotage the competition and make sure Ellen’s car wouldn’t survive. Even in my head, I fantasized about building a remote control airplane that could drop an arsenal of bowling balls on the track to crush everyone else. (To this day I still have no idea how this would’ve actually worked. At all.)

Storming off in a huff, I returned home with vengeance at next year’s race at the top of my priority list. While at a local county fair, I studied all the Boy Scouts’ top designs and how aerodynamically sound they were. I joked around with friends about how we could sabotage the competition and make sure Ellen’s car wouldn’t survive. Even in my head, I fantasized about building a remote control airplane that could drop an arsenal of bowling balls on the track to crush everyone else. (To this day I still have no idea how this would’ve actually worked. At all.) This past weekend, I heard about the horrific events of Charlottesville while waiting for my car to get some repair work done. Almost immediately, my heart sank. There was a part of me – a very cynical part of me – that wasn’t surprised at what was unfolding. At the same time, another part of me wanted to stand up indignantly and shout against the bigotry as loudly as possible. How could the neo-Nazi group gain the traction and support that they had, even to the point of inspiring other rallies elsewhere? Why weren’t more of my Christian brothers and sisters speaking out against this brand of hatred? Where was the passion over other recent travesties of injustice that may have looked less severe but were still harmful?

This past weekend, I heard about the horrific events of Charlottesville while waiting for my car to get some repair work done. Almost immediately, my heart sank. There was a part of me – a very cynical part of me – that wasn’t surprised at what was unfolding. At the same time, another part of me wanted to stand up indignantly and shout against the bigotry as loudly as possible. How could the neo-Nazi group gain the traction and support that they had, even to the point of inspiring other rallies elsewhere? Why weren’t more of my Christian brothers and sisters speaking out against this brand of hatred? Where was the passion over other recent travesties of injustice that may have looked less severe but were still harmful? If my identity is defined by my participation with the red or blue tribe, what am I really committing to? Is my response being dictated by what that tribe claims is acceptable? Or am I avoiding the awkwardness of responding because doing so fits outside the list of comfortable talking points to which one or both tribes cling? Or because I’m afraid of being labeled as something I may not be?

If my identity is defined by my participation with the red or blue tribe, what am I really committing to? Is my response being dictated by what that tribe claims is acceptable? Or am I avoiding the awkwardness of responding because doing so fits outside the list of comfortable talking points to which one or both tribes cling? Or because I’m afraid of being labeled as something I may not be? “Medicine, law, business, engineering – these are noble pursuits and necessary to sustain life. But poetry, beauty, romance, love – these are what we stay alive for!” – Dead Poets Society

“Medicine, law, business, engineering – these are noble pursuits and necessary to sustain life. But poetry, beauty, romance, love – these are what we stay alive for!” – Dead Poets Society A few years later, my family was driving through the highways of San Francisco when we passed by the now-closed Hostess Cake and Wonder Bread factory. A strangely familiar aroma wafted through the smoggy air. “That smell!” I exclaimed after getting a whiff. Among the cocktail of yeasty, jammy, artificial scents was the Alicia scent, which I finally realized was the magical smell…of Twinkies. For a wonderful, age-long moment, I was transported back.

A few years later, my family was driving through the highways of San Francisco when we passed by the now-closed Hostess Cake and Wonder Bread factory. A strangely familiar aroma wafted through the smoggy air. “That smell!” I exclaimed after getting a whiff. Among the cocktail of yeasty, jammy, artificial scents was the Alicia scent, which I finally realized was the magical smell…of Twinkies. For a wonderful, age-long moment, I was transported back. As an adult, my instinct is to bite when the lure of the pedantic is dangled. I crave a predictable life. It’s comforting when everything is boiled down to function, when I’m constantly aware of the purpose of every action or encounter, when everything carries some discernable meaning. Knowledge feels empowering, whether it’s educational (“the world works like this because of A and B”) or interpersonal (“this person works like this because they hold Opinions X and Y or have been through Experience Z”). When every question is answered, when every person’s action feeds into a preconceived narrative, when everything is explainable – the world feels safe and secure.

As an adult, my instinct is to bite when the lure of the pedantic is dangled. I crave a predictable life. It’s comforting when everything is boiled down to function, when I’m constantly aware of the purpose of every action or encounter, when everything carries some discernable meaning. Knowledge feels empowering, whether it’s educational (“the world works like this because of A and B”) or interpersonal (“this person works like this because they hold Opinions X and Y or have been through Experience Z”). When every question is answered, when every person’s action feeds into a preconceived narrative, when everything is explainable – the world feels safe and secure. What must it have been like for God to speak the universe into existence? He didn’t have to do so, after all. But He did – and even more, He took delight in what He created. He pronounced it good. And when man was created, something special happened: God was no longer alone in the creative arena. Man was made in His image, with all that urge to create, tend, and nurture. His entrusting of creation to man wasn’t just an obligatory mandate, but also an invitation to use the resources he stewards wisely, to be more Christ-like in the process.

What must it have been like for God to speak the universe into existence? He didn’t have to do so, after all. But He did – and even more, He took delight in what He created. He pronounced it good. And when man was created, something special happened: God was no longer alone in the creative arena. Man was made in His image, with all that urge to create, tend, and nurture. His entrusting of creation to man wasn’t just an obligatory mandate, but also an invitation to use the resources he stewards wisely, to be more Christ-like in the process. Scripture doesn’t go into great detail, but the unmarred relationship Adam and Eve shared with God in the sinless idyll of Eden suggests delight and intimacy were both present in the context of working to tend the garden. I love imagining God smiling down upon Adam as he discovered and named all the animals. There’s a timeless truth tucked away in the garden: God isn’t a distant deity watching us from afar. He, too, engages in work – and in the context of relationship with us.

Scripture doesn’t go into great detail, but the unmarred relationship Adam and Eve shared with God in the sinless idyll of Eden suggests delight and intimacy were both present in the context of working to tend the garden. I love imagining God smiling down upon Adam as he discovered and named all the animals. There’s a timeless truth tucked away in the garden: God isn’t a distant deity watching us from afar. He, too, engages in work – and in the context of relationship with us. In the narrative of Scripture, whenever God or an angel commands someone to “behold,” the word can usually be translated to mean “stand still and be amazed.” I know I don’t stand still often enough. I know I don’t rest often enough. But arguably saddest of all, I know I don’t stop to be amazed often enough.

In the narrative of Scripture, whenever God or an angel commands someone to “behold,” the word can usually be translated to mean “stand still and be amazed.” I know I don’t stand still often enough. I know I don’t rest often enough. But arguably saddest of all, I know I don’t stop to be amazed often enough. Last week, I had the privilege of spending time with a number of friends who were a part of a writing forum with which I was briefly involved in high school. Some of them were old friends, while others were new. Some of them were only meeting for the first time, while others were reunited across the country for the eighth time. But no matter our background, there was a camaraderie present among us that wasn’t just manufactured.

Last week, I had the privilege of spending time with a number of friends who were a part of a writing forum with which I was briefly involved in high school. Some of them were old friends, while others were new. Some of them were only meeting for the first time, while others were reunited across the country for the eighth time. But no matter our background, there was a camaraderie present among us that wasn’t just manufactured.

That’s how I’ve felt, more or less, over the past 10 or so years. Adjusting from one normal to another – hence the name “Finding Normalcy.” (Sadly, “Finding Normal” and “Finding Normality” were already taken.) Like Riley, I too once had a difficult move, only it was out of the San Francisco area and into Texas. But this recent adjustment has been about something much deeper, something on a more foundational level. It feels like the emotional equivalent of running the obstacle course on American Ninja Warrior, where your preconceptions are constantly challenged as you encounter everything for the first time. You stare up that 15-foot warped wall, build up momentum, and make a mad dash right up, only to discover that the wall was much different than you thought it was, and your strategy has to be adjusted. Okay, maybe that’s the most terrible illustration of all time, but that’s basically what it’s like to have your every assumption tested after spending so much time developing a mindset that fostered a fear of what was “on the outside.” The emotional obstacles that naturally accompany meeting another person for the first time are compounded when you have a sea of preconceptions about other people that need to be tossed to the side in the process. For a long time after passing through adolescence, I tried so hard to dive into the sorts of relationships I had missed out on as a kid – all without addressing those preconceptions and doing some very necessary heart work. And I’ve had to pay dearly for it.

That’s how I’ve felt, more or less, over the past 10 or so years. Adjusting from one normal to another – hence the name “Finding Normalcy.” (Sadly, “Finding Normal” and “Finding Normality” were already taken.) Like Riley, I too once had a difficult move, only it was out of the San Francisco area and into Texas. But this recent adjustment has been about something much deeper, something on a more foundational level. It feels like the emotional equivalent of running the obstacle course on American Ninja Warrior, where your preconceptions are constantly challenged as you encounter everything for the first time. You stare up that 15-foot warped wall, build up momentum, and make a mad dash right up, only to discover that the wall was much different than you thought it was, and your strategy has to be adjusted. Okay, maybe that’s the most terrible illustration of all time, but that’s basically what it’s like to have your every assumption tested after spending so much time developing a mindset that fostered a fear of what was “on the outside.” The emotional obstacles that naturally accompany meeting another person for the first time are compounded when you have a sea of preconceptions about other people that need to be tossed to the side in the process. For a long time after passing through adolescence, I tried so hard to dive into the sorts of relationships I had missed out on as a kid – all without addressing those preconceptions and doing some very necessary heart work. And I’ve had to pay dearly for it.

Why is it so easy to do this? Perhaps it’s because we’ve grown accustomed to dealing with the tangible, the quantifiable, and the concrete in our world – all in a very immediate sense. We can jump on Google to look up the capital of Lesotho. We can hop on YouTube to check out how to build a makeshift video studio with supplies from The Home Depot for under $100. Even when we’re dealing with something more abstract, we’ve got resources that reinforce our biases and further convince us that we’ve got it all figured out. But truly understanding another person or even ourselves, messy emotions and all, is a process. It can be grueling, time-consuming, and often frustrating – but it’s a necessary part of being human. That’s why I get discouraged when I see people practically viewed as nothing more than machines in a world of convenience.

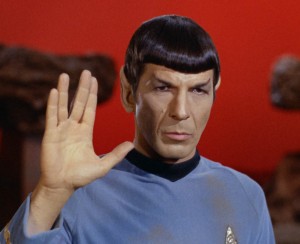

Why is it so easy to do this? Perhaps it’s because we’ve grown accustomed to dealing with the tangible, the quantifiable, and the concrete in our world – all in a very immediate sense. We can jump on Google to look up the capital of Lesotho. We can hop on YouTube to check out how to build a makeshift video studio with supplies from The Home Depot for under $100. Even when we’re dealing with something more abstract, we’ve got resources that reinforce our biases and further convince us that we’ve got it all figured out. But truly understanding another person or even ourselves, messy emotions and all, is a process. It can be grueling, time-consuming, and often frustrating – but it’s a necessary part of being human. That’s why I get discouraged when I see people practically viewed as nothing more than machines in a world of convenience. When I was about 12, while my dad was on a business trip, my mother called me over to her room while she was watching TV. “J.B.!” she shouted. “You’ve got to see this!” Excited, I ran into the bedroom and sat down in front of a screen for a documentary showing one of the Apollo astronauts on the moon. By the time I was that age, I had been exposed to quite a few movies and programs about space flight and travel in the 20th century. Tom Hanks’s HBO docudrama series From the Earth to the Moon was a big one. So was Apollo 13. I enjoyed The Right Stuff and the fun, more fictional stuff, like the old Don Knotts movie The Reluctant Astronaut. Our family had even stopped by Kennedy Space Center when we were vacationing in Florida. My dad was – and still is – especially passionate about the subject of space travel and setting out as pioneers in the final frontier, which is one reason why we’ve both grown fond of science fiction like Star Trek.

When I was about 12, while my dad was on a business trip, my mother called me over to her room while she was watching TV. “J.B.!” she shouted. “You’ve got to see this!” Excited, I ran into the bedroom and sat down in front of a screen for a documentary showing one of the Apollo astronauts on the moon. By the time I was that age, I had been exposed to quite a few movies and programs about space flight and travel in the 20th century. Tom Hanks’s HBO docudrama series From the Earth to the Moon was a big one. So was Apollo 13. I enjoyed The Right Stuff and the fun, more fictional stuff, like the old Don Knotts movie The Reluctant Astronaut. Our family had even stopped by Kennedy Space Center when we were vacationing in Florida. My dad was – and still is – especially passionate about the subject of space travel and setting out as pioneers in the final frontier, which is one reason why we’ve both grown fond of science fiction like Star Trek. This wasn’t the first time I was exposed to conspiracy theories. After becoming a Christian, I developed a rather keen fixation on eschatology for a season, though I had no discernment at all toward the subject. My parents would receive Christian book catalogs in the mail, and the first place I’d turn wasn’t always the kids’ section – it was the “Prophecy & End Times” category. I was always eager to see what new insights those books had to offer, no matter how loony or even fictional they were, especially with all the Y2K hysteria at a fever pitch. On top of that, a few of my parents’ best friends were fascinated by the subject too. I remember one night when we all went out to eat, and they were telling us about the latest book they bought, which claimed that there were “mysterious codes” in the pages of Scripture that prophesied recent news stories like the death of Princess Diana and the Oklahoma City bombings and could be found by piecing together certain letters placed at various intervals (despite the fact that the same could basically be done in the pages of Moby Dick). My parents weren’t so quick to buy into it, but I was fascinated.

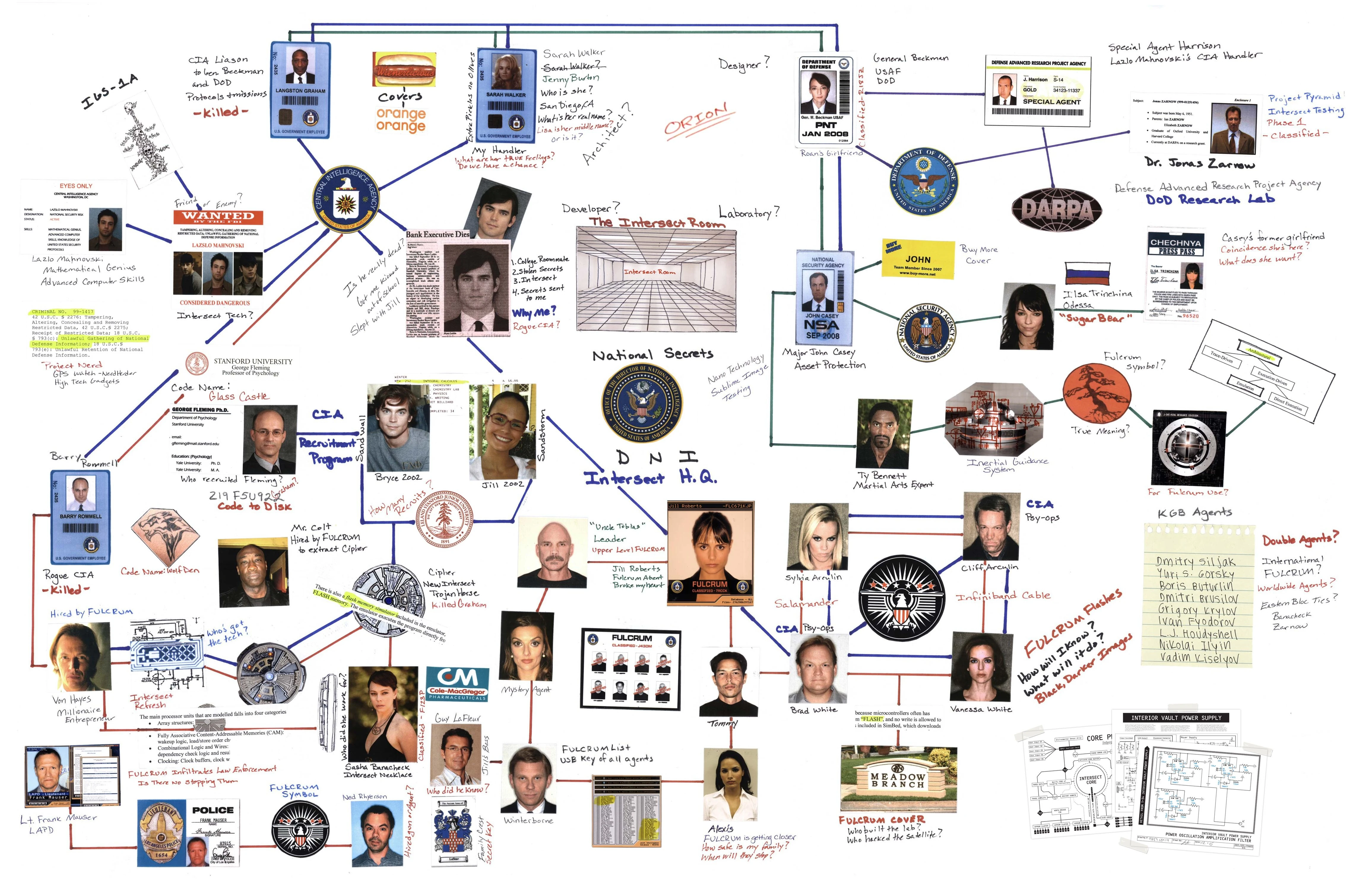

This wasn’t the first time I was exposed to conspiracy theories. After becoming a Christian, I developed a rather keen fixation on eschatology for a season, though I had no discernment at all toward the subject. My parents would receive Christian book catalogs in the mail, and the first place I’d turn wasn’t always the kids’ section – it was the “Prophecy & End Times” category. I was always eager to see what new insights those books had to offer, no matter how loony or even fictional they were, especially with all the Y2K hysteria at a fever pitch. On top of that, a few of my parents’ best friends were fascinated by the subject too. I remember one night when we all went out to eat, and they were telling us about the latest book they bought, which claimed that there were “mysterious codes” in the pages of Scripture that prophesied recent news stories like the death of Princess Diana and the Oklahoma City bombings and could be found by piecing together certain letters placed at various intervals (despite the fact that the same could basically be done in the pages of Moby Dick). My parents weren’t so quick to buy into it, but I was fascinated. We can all too easily construct narratives in which world events or cultural changes are “causes” in an equation with “effects” that are foregone conclusions, and as a result, we can feel like we’re informed when we may not be. In a previous post, I talked a bit about how our culture is very eager for control. It’s especially easy in a part of the world where many of us have convenience at our fingertips. It’s very tempting to live for results, to look for inputs that will give us the outputs we want. Similarly, it’s just as tempting to shoehorn everything going on around us into a part of a greater story with a predetermined ending. Those mysteries on TV and in the movies in which the main character has a

We can all too easily construct narratives in which world events or cultural changes are “causes” in an equation with “effects” that are foregone conclusions, and as a result, we can feel like we’re informed when we may not be. In a previous post, I talked a bit about how our culture is very eager for control. It’s especially easy in a part of the world where many of us have convenience at our fingertips. It’s very tempting to live for results, to look for inputs that will give us the outputs we want. Similarly, it’s just as tempting to shoehorn everything going on around us into a part of a greater story with a predetermined ending. Those mysteries on TV and in the movies in which the main character has a

“Are all people like this?”

“Are all people like this?”